Cause of Life

- Tayo Basquiat

- Jun 12, 2024

- 4 min read

Historic Fort Buford in North Dakota has a post cemetery, and as I toured the rows, I found humor (inappropriate, I know) in the practice back then of carving the cause of death on the grave markers. Makes sense for lots of reasons, I guess, not the least being it is a graveyard and can accomplish only so much on behalf of a person so let's at least state date of death and how that person died. What caused my laughter was the bluntness: "poisoned"; "shot by accident"; "general debility"; "inflammation of the brain"; "beat to death." Birth dates are not given but considering the times, I doubt many had seen forty circles of the sun. Several are marked "Infant" son or daughter of so and so. It was a hard life in a hard place, witness the several stones recording "suicide" as cause of death. Apart from generalized historical accounts, I know nothing about the life of Margaret Littlejohn, laundress, or Andrew Cracker, citizen, or He That Kills His Enemies, scout, apart from what my imagination might conjure.

Without doing any research into the reasons for the difference, I'll just observe that putting cause of death on gravemarkers isn't a practice I've seen in any of the other cemeteries I've visited, from those rural plots near my hometown to Pere Lachaise in Paris. The more common practice seems to be name, birth and death dates, maybe a sentiment like "beloved son" or part of a prayer. I think this different approach is probably a good move for a couple of reasons: first, is how one died really the one fact we'd want set in stone about our time on the planet? The exit? Second, these days, we'd probably just see row after after of "cancer" and "heart disease" and "car accident," but I'm also not sure how I'd feel if I was one of the exceptions, the one who died "hit by falling space junk" or some other completely random weirdness. I know, I'd be dead and so not thinking or feeling anything at all, but still, I'm thinking about it now. Giving the death blow an outsized platform, dwarfing everything else about my life with the COD, is not appealing. I don't just want to be known as "the guy killed by space junk."

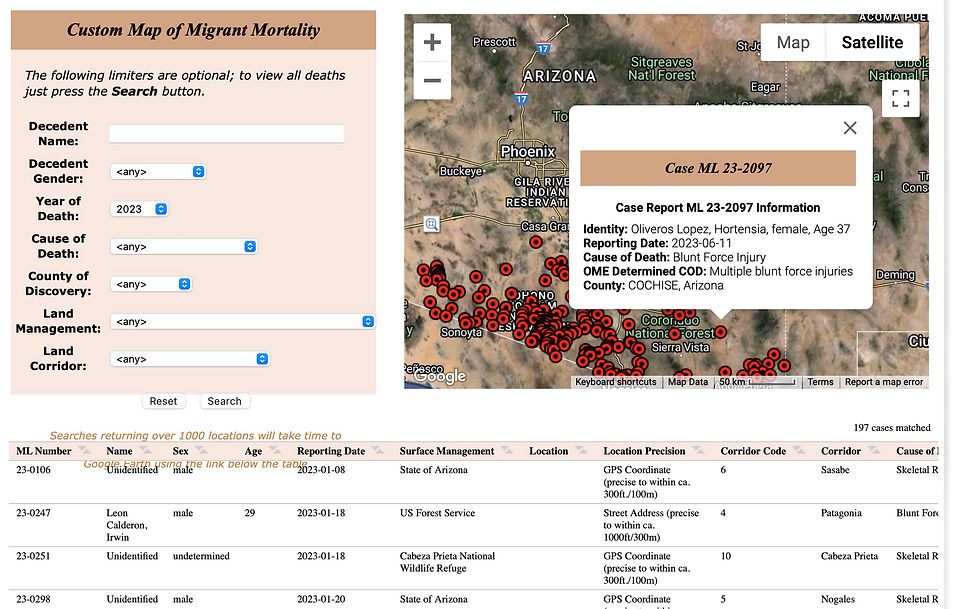

In learning about the humanitarian crisis at the U.S - Mexico border during a multi-year photography project on migrant mortality and by ongoing participation in search and rescue efforts with two volunteer groups, the Armadillos and Battalion, in Arizona, I've referred often to the website humaneborders.org. They track migrant deaths based on information from the county medical examiner:

Clicking on or hovering over one of these red dots (on their website) reveals case file information:

The COD or cause of death is usually exposure, hyper- or hypothermia, blunt force trauma, or the like, but frequently, only partial skeletal remains are found. In those cases, COD is unknown and the person unidentifiable:

After a year, all the unidentified remains are cremated and interred in a communal grave in a place like Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson (at least for those remains found in and processed by the Pima County Medical Examiner).

When I'm out on a search in a place like Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge, a place where many, many migrants have died horrible deaths but many more have died and just haven't been found, I have the sense of walking through a valley of bones. Since I've personally found so many remains, it's hard not to feel like the whole place is full of the dead, if only we could find them. My imagination works overtime, thinking how terrible it would be to die there, how easy to die there in any number of ways. But I'm also imagining their lives, or trying to: what caused them to attempt this hazardous journey? Who did they love and who loved them? What was their favorite food? What got them up and out of bed every morning? How did they celebrate their last birthday? What were their dreams? While all these deaths are terrible, the unknown and unknowable and unfound haunt me in another way, held there in the desert, unmarked graves, the very definition of lost lives.

A grim, daily-unfolding tragedy for the human family, not just at our southern border but all around the world as people flee violence or poverty or climate catastrophe or risk the little they have in hopes of something marginally better.

Since I'm not living the life of an 1870s Fort Buford infantryman or laundry dude or scout, and since I'm not a migrant trying to enter the U.S. without going through the legal channels, and since I basically have a really great life in every imaginable way, why am I blogging about cause of death and graveyards? Welcome to my wandering, musing bend of mind. (Kidding, kinda).

Here's what started all this:

Nassim Taleb has a little book of philosophical aphorisms titled, The Bed of Procrustes. This one grabbed me: "For so many, instead of looking for 'cause of death' when they expire, we should be looking for 'cause of life' when they are still around."

COD lurks as each person's unknown and unknowable, and for some of us, it is something feared, having maybe an outsized impact on our overall day to day living--though perhaps feared less is the cause of death than the dying or being dead part, or the suffering part or the unpredictability of it all or the loss of something. I've worried about them all in their turn. Taleb's aphorism is layered, but for me, it raised two questions: if others looked for 'cause of life' in me, what would they find? And, purely hypothetically: If our culture started inscribing each person's COL on their gravemarker, how would that change the experience of walking through a cemetery?

Comments